Tajikistan and Uzbekistan are restoring bilateral ties in a process that could revitalise energy supplies in the former Soviet states.

The cross-border railway between Uzbekistan and Tajikistan via Ghalaba and Amuzang on the north bank of the River Amu Darya officially reopened this week. Uzbekistan’s President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, during a visit to the Central Asian neighbour, and Tajikistan’s Emomali Rahmon pressed a button to symbolically launch the service.

The rail link closed in November 2011, when a bridge was damaged by an explosion which the Uzbekistan called a terror attack. Relations between the two countries have been strained in recent years, but have significantly improved since Mirziyoyev came to power in 2016.

During his visit, Mirziyoyev appeared to drop Tashkent’s ongoing objections to the construction of a large hydropower station near the Tajik capital, Dushanbe.

Rahmon revived a Soviet-era project to build a dam in Rogun near the capital Dushanbe on the River Vakhsh. Former Uzbek president Islam Karimov opposed the plan, saying the project could endanger the flow of rivers from the Pamir mountains to Uzbekistan’s vital cotton fields.

The informal go-ahead that Mirziyoyev gave Rahmon regarding the Rogun dam and hydroelectric power station shows how much Tashkent’s diplomacy has changed. Uzbek opposition and funding concerns were seen as the main obstacles to the project. Italy’s Salini Impregilo won the US$3.9-billion bid for the power project.

Tashkent and Dushanbe are in talks to resume electricity exchanges more than 10 years after the Soviet-era networks were disrupted. The Tajik state-owned utility Barqi Tojik said it would sell 1.5 billion kilowatt hours of electricity to Uzbekistan by September.

Seasonal shortages and limited fossil fuel supplies have hindered Tajikistan’s domestic energy transmission. The opportunity to sell excess electricity during the summer to Uzbekistan and to import much needed power during the winter could finally give the Tajiks year-round energy security. The ability to export to power-hungry Uzbekistan could also bolster the financial sustainability of Rogun.

Karimov damaged bilateral ties by supporting one of the “losing sides” in Tajikistan’s civil war from 1992 to 1997 and demarcation of the border remains incomplete.

Uzbekistan also lined several portions of its frontier with thousands of mines at the turn of the century.

Karimov visited Dushanbe twice during his presidency, in 2008 and 2014, but only for the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summits and not for a bilateral talks with Rahmon.

Mirziyoyev, on taking office, embarked on a diplomatic charm offensive with his first official visit abroad to Turkmenistan, the most isolated Central Asian country. Tajikistan was the only neighbour he had not visited, until this month.

“Geopolitics is the main problem for the project. If Uzbekistan continues on its hardline opposition, its completion could be jeopardised,” an Italian diplomat to the former Soviet states said.

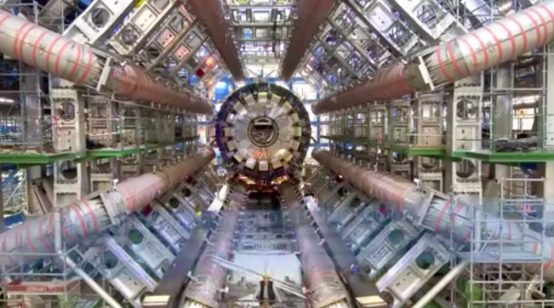

Nurek, the largest reservoir in Tajikistan. Picture credit: Wikimedia