After months of doubt, the US has agreed to increase this year’s funding for the world’s largest nuclear fusion project, meaning that the most important piece, a massive magnet being assembled by San Diego-based General Atomics, will continue without interruption.

The spending bill, passed Congress and signed by Donald Trump, included US$122 million for the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (Iter) in Saint-Paul-lès-Durance, France.

“I think it’s fantastic and shows a new commitment to fusion we haven’t seen from the government in some time,” said Mickey Wade, the fusion chief at General Atomics. “I think this bodes well for fusion research in the US.”

When completed, General Atomics’ seven 114-tonne circular modules will be shipped to the Iter site in Provence.

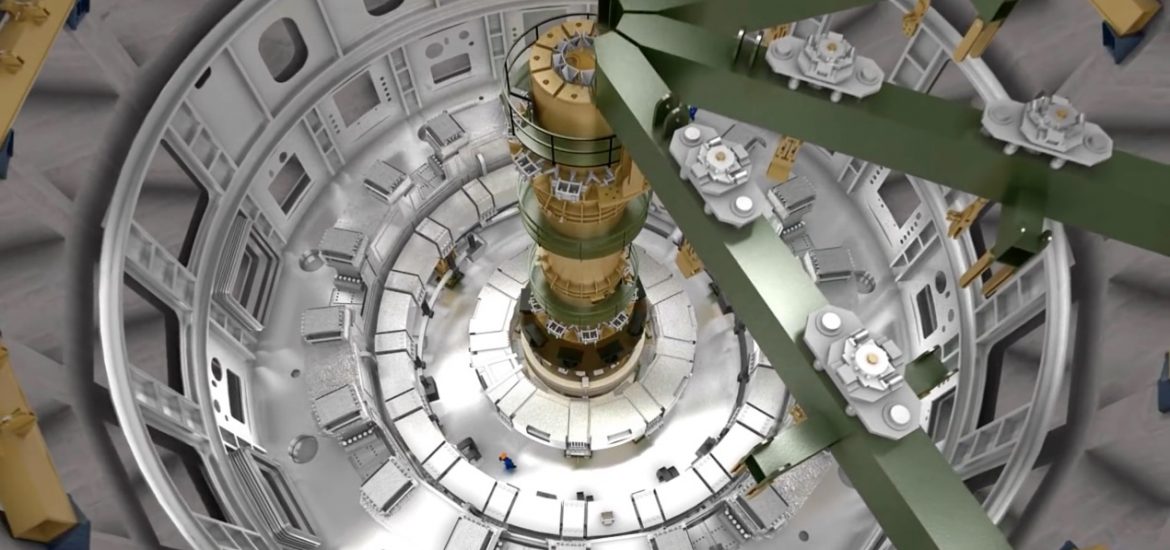

The US$20-billion project aims to control a hydrogen bomb-sized atomic reaction for a few minutes. It has a circular device, called a tokamak, that weighs three times the Eiffel Tower.

The US has contributed about US$1 billion to Iter and continued participation will cost about US$100 million to US$125 million a year for more than two decades, sparking opposition from both parties.

And Washington’s share of the project is expected to go up to about US$200 million in the 2019-20 financial year.

Participants in Iter are the EU, US, Russia, China, South Korea, Japan and India. The EU has a 45-per-cent stake with the others contributing around 9.1 per cent each.

The last-minute US budget deal avoided suggested cuts after Iter’s director general, Bernard Bigot, lobbied Congress earlier this year.

The first US magnet is due to be ready to be shipped next year and the last one is scheduled for export in 2021. Iter’s first operational test is promised in 2025.

For more than six decades, scientists have discussed nuclear fusion modelled on the sun, producing a potentially unlimited amount of energy without any greenhouse-gas emissions.

About 80 per cent of a fusion reaction’s energy is released as subatomic neutrons, which will smash into the exposed reactor components, leaving tonnes of radioactive waste.

The environmental impact of this process has not yet been assessed.

“We’re talking millions of years of fuel,” Wade said.

“I think we can conquer these challenges and be able to make fusion a realty. I tell students it’s not a matter of if we’ll have fusion, it’s a matter of when we’ll have fusion.

“I think we may have turned a corner but there’s still a lot of hard work ahead of us. I think the members of Congress for the first time really understood this is a real project and is on solid track to be successful,” he added.

Plans of the Iter reactor. Picture credit: YouTube