Since 2006, Europe has increasingly viewed eastern Mediterranean gas as a resource with huge potential to provide economic growth, mitigate climate change, and reduce dependence on Russian gas supplies. European companies have been involved in gas exploration, and the European Union has largely supported the idea of a new pipeline that connects Israeli and Egyptian fields with Cyprus and mainland Europe. But things might be changing. As global supplies of non-Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG) oversupply the market, the importance of eastern Mediterranean gas is waning for Europe. It is also proving to be a massive diplomatic headache, with rival claims by Turkey, Greece, and Cyprus on exclusive economic zones (EEZs) and gas exploration rights.

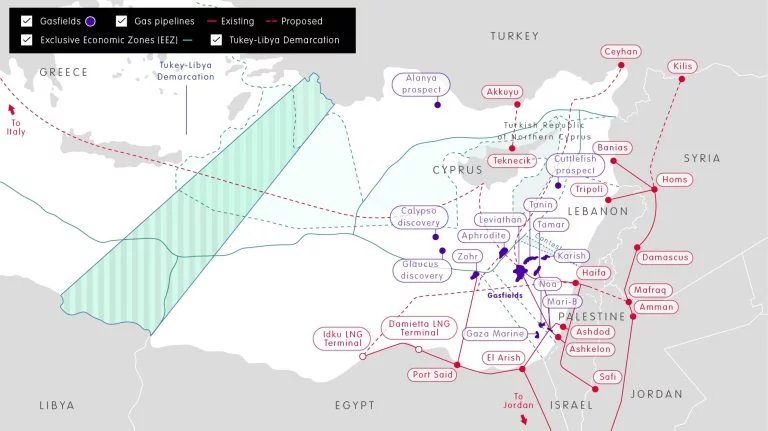

Eastern Mediterranean gas remains incredibly important for states in the region to enhance their energy security and drive economic development. The United States Geological Survey estimates that the Levant Basin – the waters of Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, Lebanon, and Palestine – has 122.4 trillion cubic feet of technically recoverable gas. To date, Cyprus, Egypt, Israel, and Palestine have discovered gas, which has stimulated cooperation between Egypt, Israel, and Cyprus. Turkey, however, disputes the right of Republic of Cyprus to explore without the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC).

Gas production would be a veritable boon to cash-poor Cyprus and Lebanon. Egypt and Israel are cooperating in trading and re-exporting gas. Turkey has practiced brinkmanship to defend what it believes are its rights to explore for gas around the most of the island of Cyprus, but would similarly benefit from discoveries of its own. Italy’s Eni has the largest stakes in the region, with massive holdings in Egypt and exploration blocks off the Republic of Cyprus and Lebanon. Other Western companies, including BG (Britain), Total (France), KoGas (Korea), ExxonMobil (United States), have joined Eni in Cyprus, while BG owns the lone field in Palestine. BP (Britain) has considerable holdings in Egypt, while Noble (United States) and Israeli companies own Israeli fields. Lastly, Russia’s Rosneft and Novatek have stakes in Egypt and Lebanon, respectively, and the country remains Turkey’s dominant gas supplier.

EEZs are not easy

Egypt, Greece, Lebanon, and the Republic of Cyprus are signatories to the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas (UNCLOS), which awards countries EEZs extending 200 miles from their shores. Yet regional powers Israel and Turkey, as well as Syria, have not signed UNCLOS and do not accept its rulings on EEZs. This complicates the path forward, to put it mildly. Lebanon disputes its maritime border with Israel, which it contends was compromised by Israel’s bilateral agreement with the Republic of Cyprus.

Turkey, meanwhile, argues that Cyprus is only entitled to a 12-mile EEZ until a resolution to the island’s status is reached, and claims that the TRNC has rights to explore in Greek Cypriot waters. To defend its position, Turkey has deployed exploration and drilling ships to Greek Cypriot waters and sent naval vessels to harass international companies’ operations. Much as China has done in the South China Sea, Turkish brinkmanship has frozen the development of gas in disputed waters.

Production within these disputed waters would constitute a red line for Turkey. Since losing the oil-rich Mosul province after the First World War, Turkey has been unwilling to let others exploit oil or gas to which it believes it has rights. In early 1974, Greece began exploring for oil in the Aegean Sea, which escalated tensions over Cyprus and culminated in Turkey’s invasion and the establishment of Turkish Cyprus. Turkey’s willingness to assert itself on the Libyan battlefield should remind European nations that it would do the same with eastern Mediterranean gas.

Spokes of the wheel

Pipelines offer the best economies of scale for exporting gas, and Egypt, Israel, the Republic of Cyprus, Greece, and Italy all support the construction of the subsea EastMed gas pipeline to Italy – a move that would cut out Turkey. However, Libya and Turkey delineated their maritime border in November 2019, blocking the pipeline’s path. Turkey’s move was diplomatically clever, but the estimated $6-7 billion EastMed pipeline was never an attractive investment, and no capital has been committed.

The Republic of Cyprus already has agreements to send future exports – beyond what the island consumes – to US allies Egypt and Israel for re-export. Egypt and Israel have cooperated on hydrocarbons since the Suez Canal reopened in 1975, and Israel started exporting gas from its Leviathan and Tamar fields to Egypt in January 2020. Egypt’s two Mediterranean LNG export terminals at Idku and Damietta can flexibly serve Europe, but are less commercially advantageous for Israel than a pipeline straight from the Mediterranean fields. Exports from Idku rose 151 per cent between 2018 and 2019. Damietta is slated to come back online in July 2020.

In 2016, Israel discussed sending gas by pipeline to Turkey, the largest nearby market. This pipeline would be cheaper than the EastMed project, but significant political challenges remain. Israel, for its part, seeks as many gas export options as possible, which would bestow commercial advantages in pricing and security against disruptions in its current destination markets, Egypt and Jordan.

Foreign companies and great powers

The interests of commercial players – many of which are European and enjoy government backing – also shape the landscape. Italy’s Eni has the largest stakes of any company, and is especially strong in Egypt, where it operates the supergiant Zohr field and others. Egypt has the largest reserves in the region at 75.5 trillion cubic feet. BP is also well positioned in Egypt, while Total has been the most active explorer in the Republic of Cyprus and Lebanon, alongside Eni. All three European companies want to enhance their gas portfolios and diversify away from oil, a step that also represents strategic priorities for their respective governments as they look to advance national economic interests but also strengthen European energy security. Noble operates the major fields in Israel, but majority ownership is with Israeli companies.

Ever conscious of protecting its European market share, Russia has taken its own commercial stakes in eastern Mediterranean gas. Russian companies have producing shares in Egypt and exploratory blocks in Lebanon and already supply the majority of Turkey’s gas imports. To shore up market share, Russia offered it a 6 per cent discount in early 2020 on gas through the newly inaugurated TurkStream pipeline. Russia is a natural ally with Turkey in eastern Mediterranean gas, and rumours, later shot down by Vladimir Putin, emerged in January 2020 that Russia might recognise the TRNC.* Operator.

At the same time, US exports of LNG to Turkey have grown spectacularly since 2015, including by 30 per cent between 2018 and 2019. Since the US is now a gas exporter, it views eastern Mediterranean gas somewhat similarly to the way Russia does. Neither country is eager to see new volumes come online and compete for European market share. During the Trump presidency, the two countries have indirectly cooperated in restricting oil supplies from the market to gain market share. However, both want to extend the era of hydrocarbon dominance of the global energy system, and keeping the world well supplied is the most effective method for locking in future demand. These competing interests help explain each country’s ambivalent energy diplomacy and quiet statecraft concerning eastern Mediterranean gas.

In January 2020, Turkey began to deploy gas-exploration vessels close to its new maritime border with Libya. This brings Turkey into further proximity to Italy, which, like Turkey, backs Libya’s Government of National Accord. This raises the potential for new cooperation on eastern Mediterranean gas more broadly.

Conclusion

Historically low gas prices and a supply glut in Europe make eastern Mediterranean gas less commercially attractive. The coronavirus will further depress new investment. In April 2020, ExxonMobil postponed drilling in Cyprus to 2021, and, in early May, Eni and Total followed suit. Due to its methane emissions, gas faces further headwinds from those concerned about climate change, although the advancement of blue hydrogen technology, which captures and transforms methane into hydrogen, could help. In 2019, the West and its Asian allies committed to the long-term development of hydrogen as an alternative to a renewables-only strategy for the energy transition. In the future, Europe will still want eastern Mediterranean gas, but not as urgently as it once did.

This piece was originally published on 26 May 2020 by the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR) as part of a report entitled Deep sea rivals: Europe, Turkey, and the new eastern Mediterranean conflict lines.

Did you like it? 4.4/5 (27)