In early 1959, oil prices were low and falling. British Petroleum had cut prices. The United States had instituted import quotas, limiting the amount of foreign oil that could enter the world’s largest market. Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, Venezuela’s Minister of Mines and Hydrocarbons, resolved to do something. At the Arab Oil Congress and alongside oil ministers from Iran, Iraq, Kuwait, and Saudi Arabia, he began laying the seeds for the creation of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) in 1960. OPEC got off to a slow start. But by the 1970s, it had supplanted the United States as the most powerful force in the global oil markets.

Now, the United States is trying to set the terms of oil markets again. On January 28, the Trump Administration implemented sanctions against Venezuela’s national oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PDVSA) on the heels of opposition leader Juan Guaidó declaring himself the rightful president of the country. Washington says that its policy is designed to restore democracy to Venezuela. The current president Nicolás Maduro rejects these calls, finding backing in Beijing, Moscow, Tehran, and Ankara.

But simply invoking “democracy” obfuscates the real reasons underpinning U.S. policy. One of these is oil. Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves. It is now the third major oil producing country, after Iran and Russia, to be targeted by U.S. sanctions. The sanctions also reflect a timeless tenet of U.S. foreign policy: the Western Hemisphere is America’s backyard, and other powers should stay out. The Trump administration sees an opportunity to install a friendly regime in Venezuela and ensure U.S. dominance in oil and in the Western Hemisphere for the next generation.

The Trump Corollary

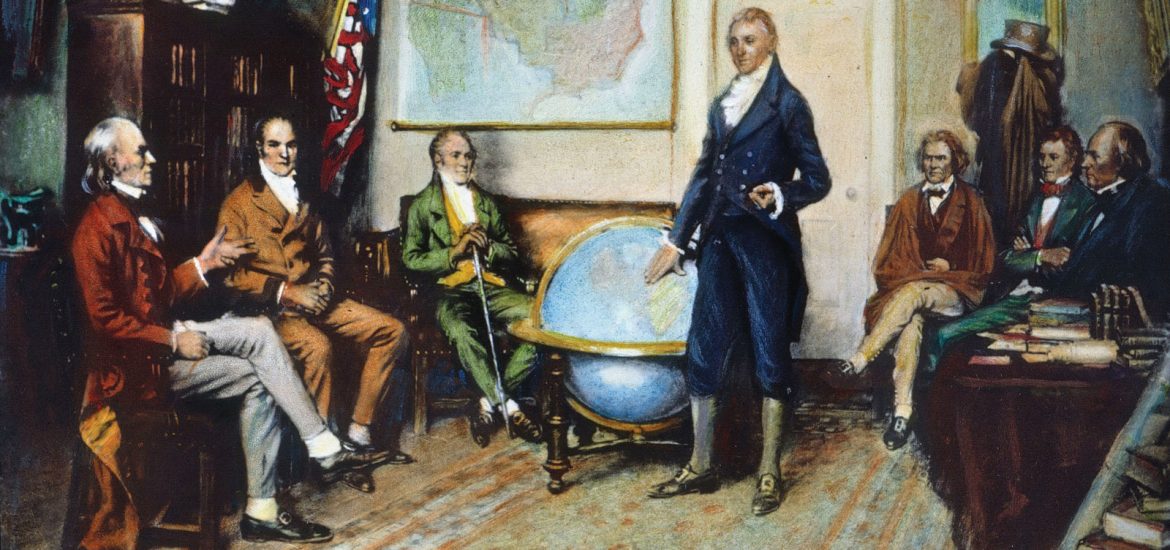

When it was first announced in 1823, the Monroe Doctrine was toothless. President Monroe verbally warned European powers against interfering in the affairs of the recently independent states of Latin America, but he lacked the military or economic power to back it up.

By the turn of the twentieth century, it did. As Venezuela became unable to repay loans to European powers, Britain, Germany and Italy launched a naval blockade to force the issue. Quiet American diplomacy ended the crisis and, in 1904, President Roosevelt announced what became known as the Roosevelt Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine. The United States would intervene to assure the repayment of debts by Western Hemispheric nations.

The United States no longer needs to verbalize the Monroe Doctrine. During the Cold War, Republican presidents Eisenhower, Nixon, and Reagan fought against Soviet-backed, Communist-inspired groups in Latin America.

The newest challenge to U.S. dominance came with Hugo Chavez’s election in 1998. Chavez launched the so-called Bolivarian Revolution, cultivating other leaders including Bolivia, Cuba, and Ecuador. China and Russia, meanwhile, offered financial support. Maduro is Chavez’s heir.

Trump has followed his predecessors by championing right-wing governments in the region, see his support for Brazil’s Bolsonaro most recently, and the Lima Group, which backs Guaidó and a peaceful resolution to the crisis. In February 2017, then U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson quite openly discussed reviving the Monroe Doctrine to counter China’s rising influence in Venezuela and South America.

The Trump Administration is therefore borrowing from an old and trusty playbook to reassert U.S. dominance in the Western Hemisphere.

Distressed assets

The parallels between 1902-1904 and today are the most striking. Estimates place Venezuela’s outstanding external debt at close to $100 billion, if not higher, of which $20 billion is owed to China and $2.3 billion to Russia. If Maduro goes, these debt payments will likely be forgiven, leaving these powerful creditors out of luck.

Yet the crux of U.S. interest in Venezuela is oil. The demise of its oil production under Chavez was a national tragedy and caused its current troubles.

Production has nosedived since the beginning of 2017.

Next generation oil

Reviving the industry will take years of good governance. The key is being in the catbird’s seat when it does return.

U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton explained this quite clearly in an interview with Fox News: “We’re looking at the oil assets. That’s the single most important income stream to the government of Venezuela…We’re in conversation with major American companies now…It will make a big difference to the United States economically if we could have American oil companies really invest in and produce the oil capabilities in Venezuela; it will be good for the people of Venezuela, it will be good for the people of the United States.”

U.S. companies helped birth the Venezuelan oil industry in the 1910s. Despite its OPEC leanings, Washington partnered with Caracas during the oil boom from the 1950s to 1970s, and American companies remained present in the country ever since. Venezuela played a vital role in preventing shortages during the Cold War while the United States was the world’s largest oil producer. Chavez, on the other hand, used Venezuelan oil as a political weapon when the United States depended on it.

Now, with the U.S. having ascended once again to the position of top producer, Venezuela has little leverage, even if its oil industry were healthy. Its appeals for help from OPEC have gone answered. The United States even imports 500,000 barrels per day of Venezuelan sour heavy crude for its own refineries, but can fill this gap elsewhere. In many ways, Bolton is right. It’s hard to see how the country can revitalize its oil industry without U.S. backing.

No pain no gain

The sanctions will weaken the Maduro regime, but will they topple him?

It is unlikely in light of past experience. Countless times, U.S. officials have claimed that economic pressure will force regime change only to discover that regimes are more resilient than expected. Moreover, Venezuelan citizens will be the ones experiencing the pain of these sanctions. It is possible that those who oppose Maduro don’t even want them

This pain is not of a concern in Washington, where the foreign policy community has unified behind the sanctions. They are a predictable tool, blunt in purpose, cheap to implement, and with a clear goal in mind: to gain influence over a weakened country in America’s own backyard that has enormous oil reserves.

Very interesting, my friend. The question, now, is who is going to give up first, the US or Chavez? In the meantime the Venezuelans get hungrier by the day. It’s an unnecessary tragedy that may be costing lives, and wasting resources.