On April 4, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) celebrated its 70th birthday in Washington in rather ho-hum fashion. The attendance of only foreign ministers seemed to capture the mood. In different times, a decennial milestone for the world’s most successful military alliance no less would have involved the presence of heads of state.

Yet we should filter out noise from reality. On Google Trends, “end of NATO” hits its peak frequency every year in April or May on the alliance’s anniversary. A slew of analyses last week, in fact, argued the opposite. As Russia continues to threaten Europe’s eastern flanks and scramble European hearts and minds through cyberspace, NATO’s raison d’etre has become, if anything, clearer, and the alliance stronger.

Energy security amplifies these arguments. Nord Stream II is dividing Europe economically, but the passion against which both the United States and other EU members oppose the project is strengthening trans-Atlantic ties. Moreover, energy trade, especially in fossil fuels, has grown since the mid-2000s, building concrete security and commercial ties. Meanwhile, like-minded policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic are continuing to cooperate on renewables and climate with a long-term view in mind. Long the lifeblood of the alliance, energy continues to make NATO indispensable.

Oily foundations

Nuclear weapons and oil were the concrete commodities that undergirded NATO’s creation. The formalization of the alliance came two months after the Soviets detonated their first nuclear weapon in February 1949.

Yet oil created inroads for the alliance before nuclear weapons. The United States issued its first foreign aid to Greece and Turkey in 1947 after Stalin backed Communist groups in the Greek civil war and threatened to take the Turkish Straits and disrupt the free flow of oil. Then, during the brutally cold winter of 1947-8, the United States launched Marshall Plan aid, over ten percent of which was oil. U.S. and British companies also made deals in 1948 to share Middle East oil concessions and safeguard Europe’s supplies. It’s often forgotten that Europe’s miraculous economic recovery in the 1950s and 1960s owes much to cheap Middle East crude.

Western companies and governments also built an extensive network of intra-European oil pipelines to guarantee that NATO’s planes, tanks, and ships would be well supplied in case of a military conflict with the Soviet Union. The United States even prioritized sending steel to Europe over Middle East pipelines in the early 1950s for this reason.

The Soviet Union tried consistently to break into European oil markets after the Suez Crisis in 1956-7. By offering lower prices, it achieved marginal success, mostly in Mediterranean countries such as Italy. After it completed the Druzhba oil pipeline in 1964 to central Europe, it had more success. Yet Soviet oil remained marginal in Europe’s overall supply, and remained so through the 1970s. U.S. oil production today continues to secure Europe’s oil supplies in the case of a military conflict.

Gas is different

The Soviet Union was the first to gain a dominant position in European gas and remains ensconced as such today. It began building pipelines to Central Europe in the late 1960s, but gas was of marginal strategic importance. Europe even bucked the United States in the early 1980s on a new Soviet gas pipeline, but this did not undo NATO, it only helped Europe switch to gas from coal.

Today’s gas competition is centered on Central and Eastern European countries that Russia ruled during the Cold War. NATO welcomed many of these countries from 1999-2009. Europe’s imports of U.S. fossil fuels have been steady or grown since this expansion.

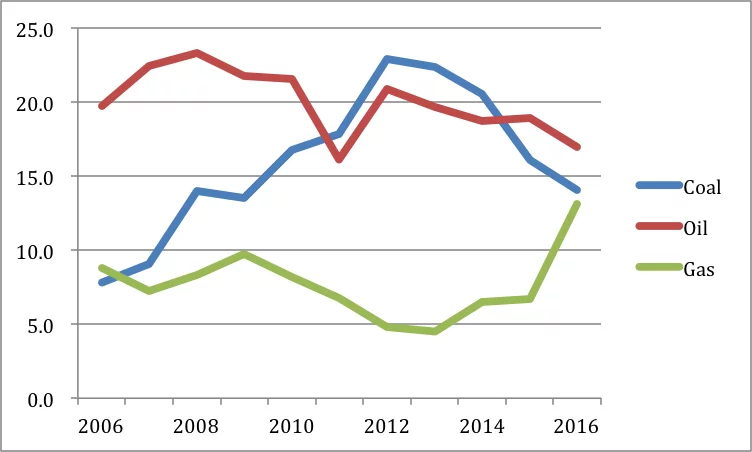

U.S. percentage of Europe’s overall imports of coal, oil, and gas

Source: Eurostat. Figures for coal are U.S.-only, for oil and gas, all others, the predominant supplier being the United States.

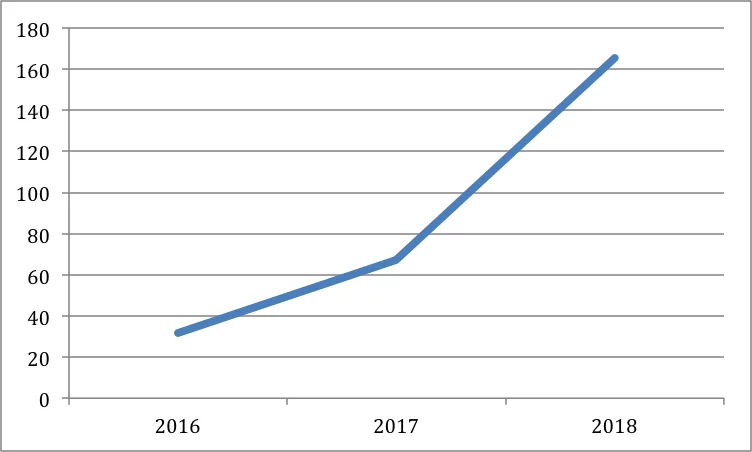

The above figures are only available through 2016. Data on U.S. oil imports, however, shows that they have surged since then.

U.S. oil import volumes (million barrels) to Europe, 2016-18

Source: Eurostat.

So have gas imports, as LNG.

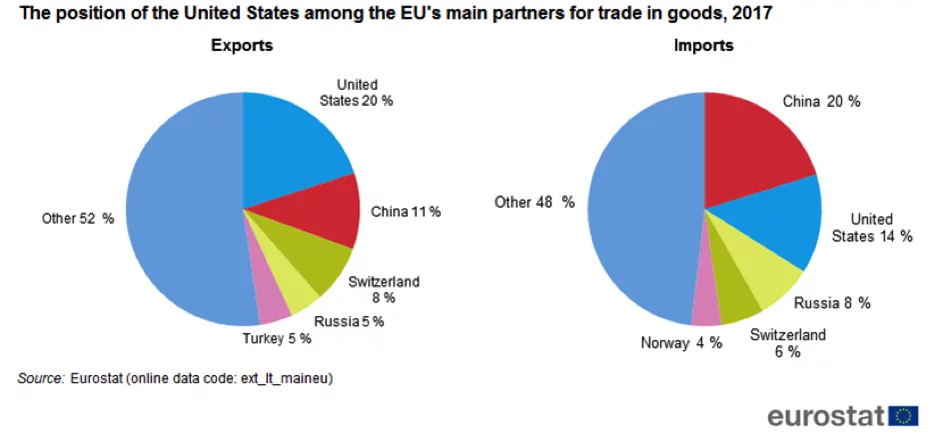

Add to all this, the United States was Europe’s largest trade partner in 2017.

NATO’s economic health, in other words, is robust.

It is true that many Central and Eastern European countries have assumed a pro-Russia posture. It is also unsurprising that Russia has sought to reassert dominion in them.

But fighting for their energy security provides NATO with a clear objective, something underscored by Washington’s opposition to Nord Stream II. Politically, despite Trump aggravating trans-Atlantic ties, there is resolute, bipartisan support in Washington for the alliance. In January 2019, the House of Representatives voted 357-22 to bar Trump from leaving NATO.

Clean energy NATO

Furthermore, Trump’s policy of energy dominance will likely be replaced in 2020 if he loses the election. It’s not so much that U.S. oil and gas exports would decline, but renewables and the fight against climate change would receive a boost. Early Democratic candidates recognize that climate change is a political winner, not least because it speaks to the generational divide between younger and older voters.

Regardless of the election, a more balanced approach is already emerging in Washington, one in which it would work more closely with NATO on renewables, energy efficiency, nuclear, smart grids, and climate. Renewables, after all, are excellent additions to an energy-secure portfolio. Imports of fossil fuels are expensive. Countries not only produce renewables domestically but renewables also lend themselves to technological and financial symbioses with newer technologies.

Suggesting the end of NATO is almost as silly as suggesting the end of OPEC. But, at this point, I would bet, based on current trends and the long-term structural forces in energy markets, that NATO even outlasts OPEC. Energy is the lifeblood of every alliance.

Did you like it? 4.5/5 (22)