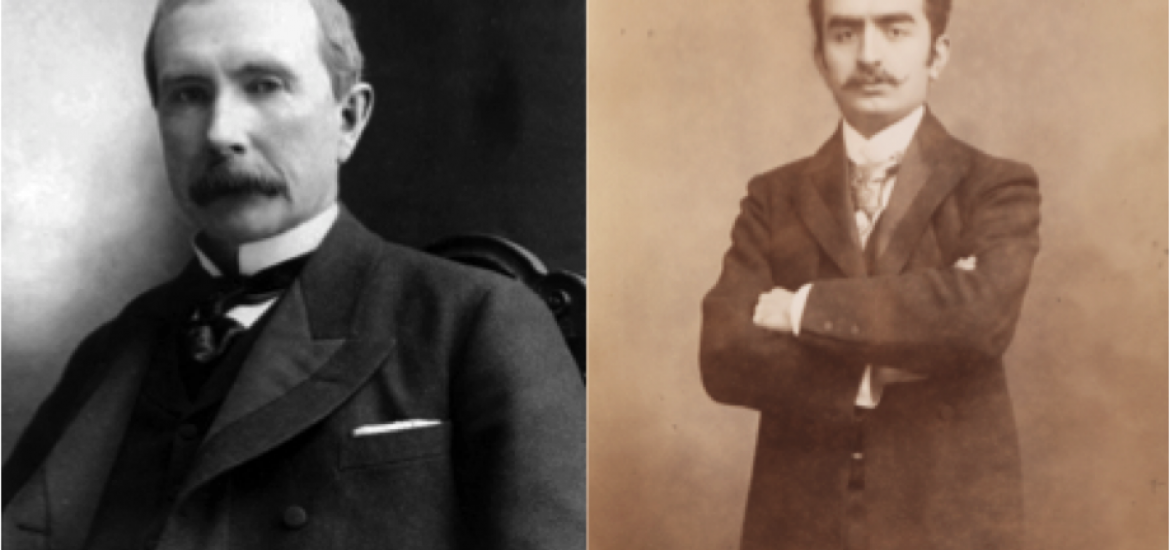

The modern oil industry has seen numerous pioneers. In the United States, John D. Rockefeller did more than anyone to modernize the industry through his dominant position in refining and marketing. In the Middle East, Calouste Gulbenkian helped bring together British, Dutch, and German interests to explore in the Ottoman Empire and later in Iraq.

In a sign that the oil era is no longer ascending, the Rockefeller Family Foundation announced in May 2016 that it would withdrawal all investments in fossil fuels, arguing: “There is no sane rationale for companies to continue to explore for new sources of hydrocarbons.” Last week, Partex, the company that Gulbenkian started and grew into a veritable giant from the 1950s to 1970s, announced that it is holding talks to sell its fossil fuel assets.

These moves do not undermine the dominance of fossil fuels in the global energy system in any way. But it is interesting that these entities no longer view their assets as untouchable. The ascent of renewables is making entities with long-term investment horizons think twice. They also beg the question about how individuals can shape a global energy system that is far more complex than the early decades of the oil era.

Veritable giants

Rockefeller’s dominance of the U.S. oil industry is one of history’s single greatest business performances. He entered the refining sector in 1870, just a decade after the first application of modern drilling techniques in 1859 in western Pennsylvania. Rockefeller quickly became dominant in refining Pennsylvania crude into kerosene, an illumination fuel. He moved into the oil transportation sector through favorable deals with railroads during the 1870s-1890s, becoming the major exporter of U.S. oil to Europe and Asia. Smaller players resented his monopolistic tactics, but the Standard Oil Company helped create a global market for oil. The U.S. Supreme Court disbanded Standard in 1911. Three of these smaller entities became Seven Sisters: Exxon (Standard Oil Company of New Jersey), Mobil (Standard Oil Company of New York), and Chevron (Standard Oil Company of California).

Gulbenkian had a similar story. He studied oil engineering in the 1880s at King’s College London and was commissioned by the Ottoman Sultan in 1892 to study the oil deposits in the Mosul province of Iraq. An Armenian, Gulbenkian fled his hometown of Istanbul in 1896, but his peripatetic life helped him meet influential London bankers. In 1912, he helped launch the Turkish Petroleum Company, a conglomerate of British and German interests to explore and produce oil in the Ottoman Empire. Gulbenkian received a five percent share in the TPC, which he retained after the war along with the moniker of Mr. Five Percent. His company Partex participated in the production of Iraqi oil from Kirkuk until 1972, after which it invested around the globe.

A green Rockefeller or Gulbenkian?

The Rockefeller and Gulbenkian stories are of brave individuals building global markets from scratch. Rockefeller thrived in a vacuum of state power. The U.S. government did not regulate the oil industry until it considered transitioning its navy to run on oil rather than coal in the 1900s. Gulbenkian also operated on a blank canvas and allied himself with powerful nations and financial houses in London to create a tremendous fortune.

It seems unlikely that an individual in today’s age could rise to such prominence and wealth in the energy system. Nation states now dominate domestic energy industries unlike in those earlier eras. As the growth in energy consumption is set to come more from renewables than any other source, it also seems unlikely that an individual could gain control over production in the same way. Every country or jurisdiction, after all, could, with the proper investment, develop its renewable energy production.

Yet it is worth recalling that the coal, oil, and gas era started in similar fashion. Localized production gradually expanded to regional and global markets through improvement in the transportation sector. The advent of steam-powered ships in the 1870s, oil supertankers in the 1960s, and liquefied natural gas tankers in the 2000s globalized each source. New battery technologies could do the same for electricity.

Maybe Musk

Elon Musk seems the most likely to fit the fold of modern day Rockefeller and Gulbenkian. He has championed electric vehicles through Tesla and the large-scale batteries that can harness and store wind and solar power. On February 6, Musk succeeded in putting the world’s most powerful rocket into orbit as part of his company SpaceX. It would be unwise to bet against a Green Rockefeller such as Musk, a South African, emerging in the United States, where the barriers to enter markets are relatively low. It is possible to envision how the control of batteries, either over their inputs or technology, could bestow similar degrees of market power.

We all have a collective desire to use more renewable energies to arrest the pace of climate change. Yet we are hampered by inertia and the lack of political leadership to take decisions that might arrest economic growth. We may need visionary leaders like Rockefeller and Gulbenkian to seize market opportunities if we are to resolutely move away from fossil fuels.