An agreement on the use of nuclear energy for peaceful purposes, signed between Uzbekistan and Russia in late 2017, has come into operation this week.

The project could provide Tashkent with much-needed energy security and potentially relax tensions with its Central Asian neighbours as it pushes ahead with efforts to boost regional cooperation.

The creation of a national infrastructure, training of Uzbek staff, construction of nuclear power stations, research reactors and support throughout the life cycle were agreed in the deal.

The agreement also covered the exploration and development of Uzbek uranium deposits, reclamation of uranium tailings, production of radioisotopes and their use in industry, medicine and agriculture, scientific and research, according to the Russian authorities.

The agreement envisages bilateral working groups for the implementation of projects and research.

Russia said it offered to build the former Soviet satellite state a nuclear power station with two new generation power units for energy-deprived Central Asian nation.

Rosatom director general Alexei Likhachev announced during a visit to Uzbekistan that the atomic giant would build the most modern two-block nuclear power station in the country.

“Our proposal is to build a station of two modern blocks of the three-plus generation VVER-1200 here in Uzbekistan, in the time that the Uzbek side considers acceptable. Our experience in the construction of such stations is very solid,” he said during the visit.

The project would ensure Uzbek energy security, he added.

The venture was due to create around 5,000 to 6,000 jobs during the construction process and have 1,500 to 2,000 staff when operating.

Energy cooperation is a key issue in Central Asia where Soviet power networks broke down acrimoniously after the fall of communism.

Since the appointment in December 2016 of Uzbek President Shavkat Mirziyoyev, Tashkent has focused on rekindling regional ties, which were long neglected by his veteran predecessor Islam Karimov.

Uzbekistan has dropped its longstanding opposition to hydroelectric projects in Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan. Karimov once threatened Tajikistan with war over the its proposed construction of the Rogun dam, claiming it would hamper water supplies to Uzbekistan’s key cotton sector.

There is no organisation that binds Central Asia, unlike the European Union or Southeast Asia’s Asean. The Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and the Commonwealth of Independent States are both dominated by the external powers of China and Russia, respectively.

Central Asian frameworks, like the Interstate Commission for Water Coordination, have also failed to mitigate bilateral disputes or build a sense of national unity.

Mirziyoyev, during his address at the United Nations General Assembly last year, said: “Uzbekistan considers the region of Central Asia to be as the main priority of its foreign policy.”

Central Asia’s first regional summit in almost a decade took place last month, with four of the five leaders in attendance. Increasing energy cooperation will be one sign that the region is coming together.

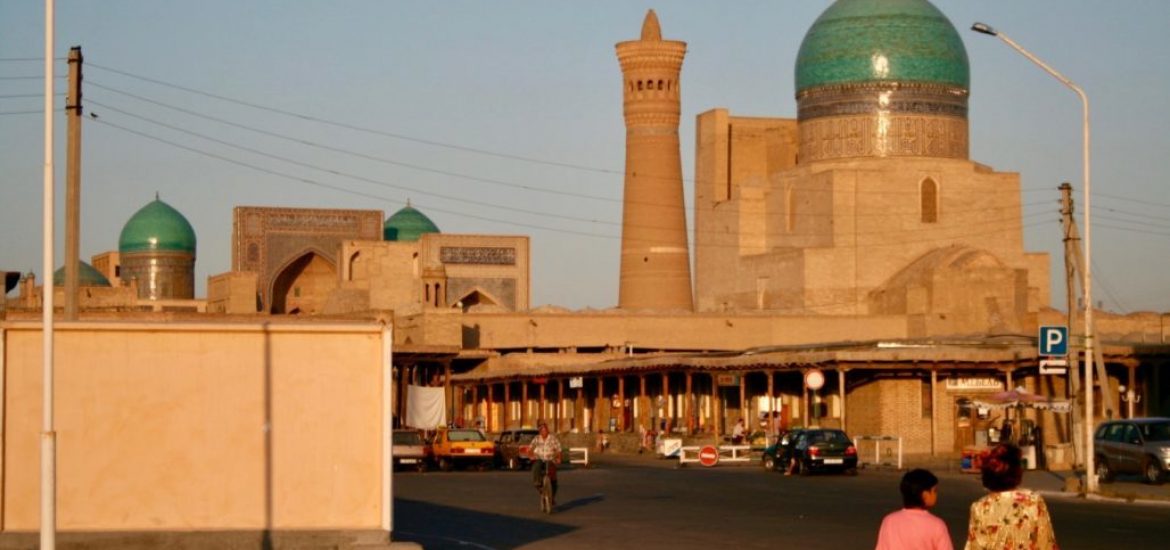

Uzbekistan hopes an element of its glorious history can be restored. Picture credit: Energy Reporters